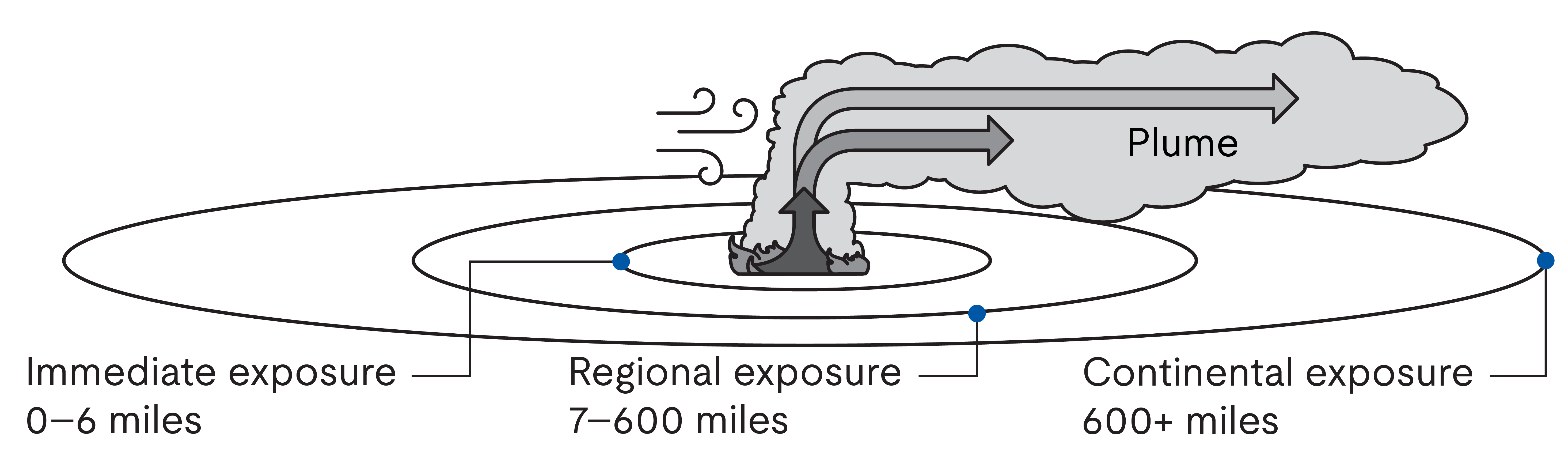

As fuel, such as trees, structures, and vehicles, burns during a fire, it releases emissions like particulate matter and chemicals into the atmosphere nearby. These emissions form a giant mass of pollutants called a plume.

The plume evolves over time and changes its chemical nature through a process called atmospheric transformation. These changes occur as the emissions cool in the atmosphere and react with each other and with sunlight. The process continues as the plume mixes with other urban pollutants in the air, such as from industrial processes and cars.

As the plume moves further downwind, the process slows and particles ultimately begin to fall from the sky. This means people are exposed to a variety of different pollutants, both near and far from the original fire. While larger particles may be visible as ash, smaller particulate matter (PM2.5) may be harder to detect and can take longer to settle as dust.

Since plumes can travel great distances, even spanning across entire continents, exposure to emissions occurs at different scales, impacting how people come in contact with pollutants. While there is much to learn about the health effects from an atmospherically transformed plume at regional and continental scales, more is known about the health effects closer to the initial source.

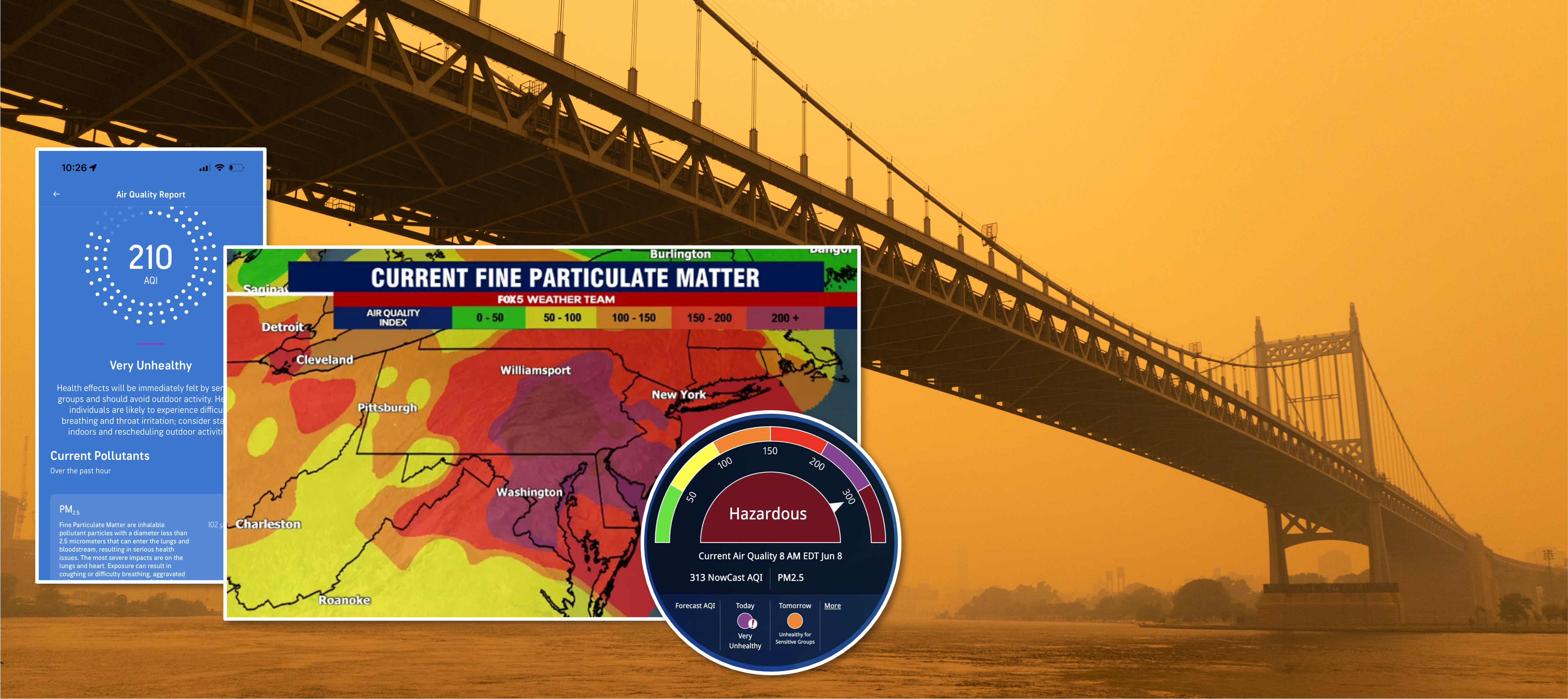

Wildfire emissions do not just impact the local community. They can impact large areas of the U.S. as well as the globe, ultimately impacting millions of people. A recent example of this occurred in Summer 2023, when major parts of the U.S. experienced hazardous air quality due to Canadian wildfires.

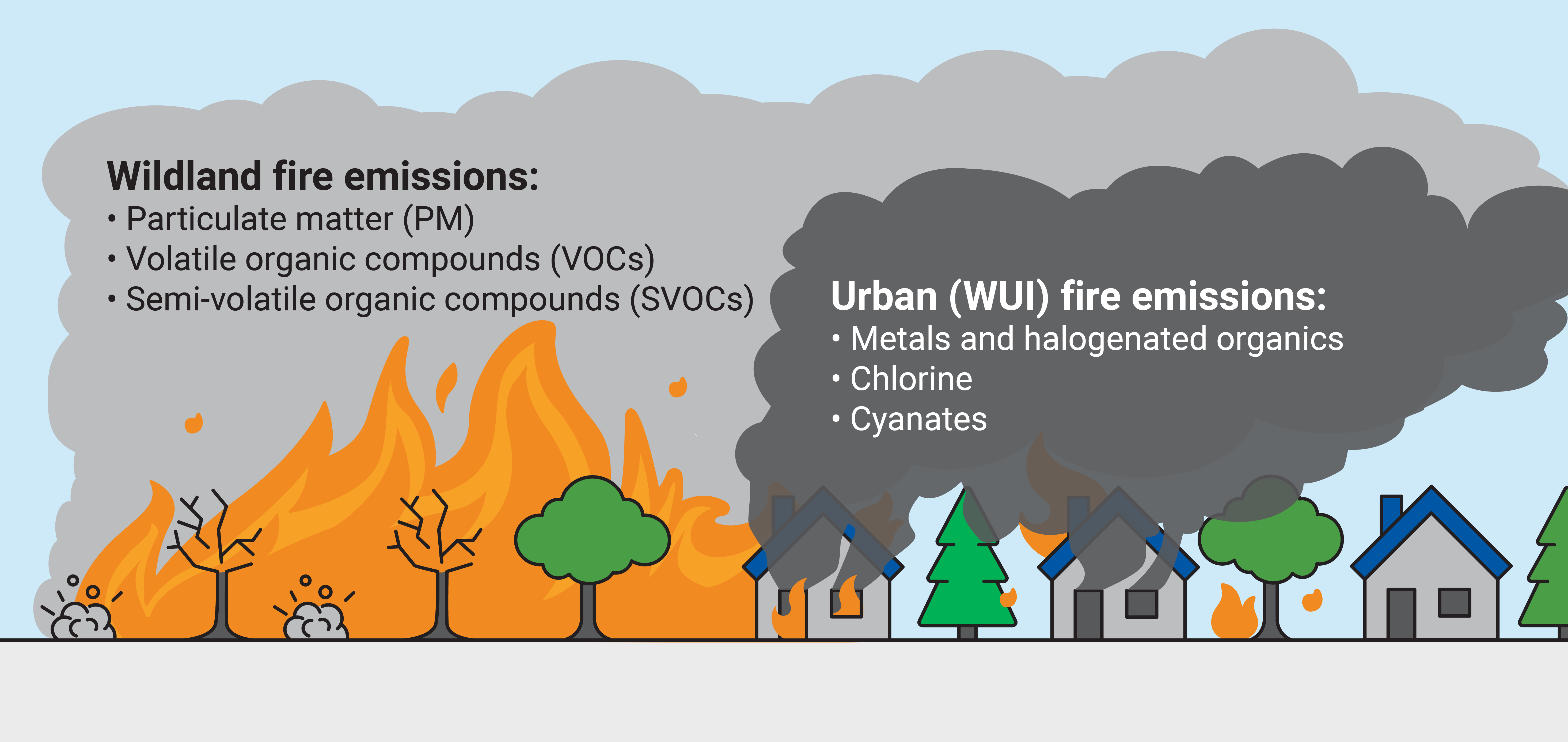

All wildfires produce smoke and a large mix of pollutants, including:

These emissions represent a vast array of chemicals, some of which are acutely toxic, irritants, and known carcinogens. All of these compounds are emitted from natural vegetation like trees, shrubs, and grasses when they burn.

But when a wildfire spreads to include the urban fuels in the WUI, an entirely different mix of pollutants is expected to be found because these fuels are chemically very different from vegetation. This different mix of pollutants is expected rather than known because there is limited research on WUI fire emissions.

The built environment contains things like metals, PVC (which contains chlorine), nylon (which has high nitrogen content), manufactured woods (which can generate cyanates when burned), and many other compounds, so it stands to reason that emissions from fires in the WUI contain a much more complex and potentially toxic mix of pollutants.

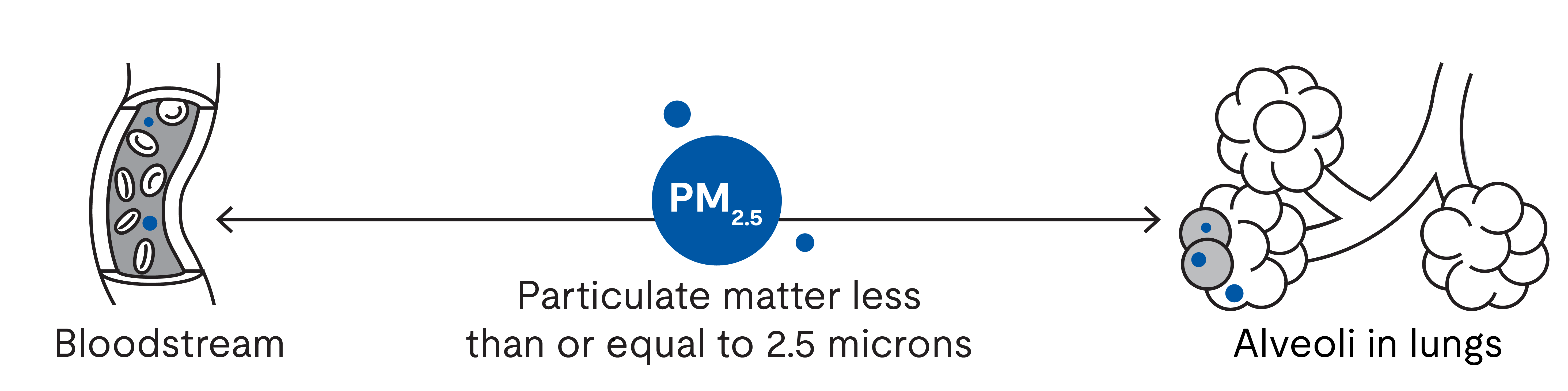

While emissions contain a complex mixture of pollutants, particulate matter is a primary concern in all wildfires. When inhaled, PM2.5 (particulate matter that is 2.5 microns or less in diameter) can penetrate deep into the lungs and may even infiltrate the bloodstream.

How small is 2.5 micrometers? The average human hair is about 70 micrometers in diameter – making it 30 times larger than the largest fine particle.

Studies have linked PM2.5 from wildfires to health issues such as exacerbation of asthma, COPD, premature death, and cardiovascular disease, such as heart attacks and strokes.

Certain members of the population may be more sensitive to exposure than others, such as children, older adults, and pregnant women. Additional examples include people who have:

Since WUI fires cannot be left to burn out naturally, nearby workers, including firefighters, emergency response teams, and clean-up recovery crews are increasingly exposed to emissions, smoldering and resulting residues, and dust. Additionally, outdoor workers in surrounding areas, such as farmers and landscapers, may be at a greater risk.